Labyrinth Typology

Text and images by Jeff Saward and Yadina Clark

The description and naming of different types of labyrinths is something that has intrigued people for many years and is the subject of much discussion to this very day. The classification and typology of labyrinths has evolved over the past several decades due to increased worldwide awareness and use of labyrinths, international communication, and analysis ranging from casual interest to intense study. Just as labyrinth design has had periods of innovation, we are in the midst of a significant moment in labyrinth typology.

100 Years of Labyrinth Typology

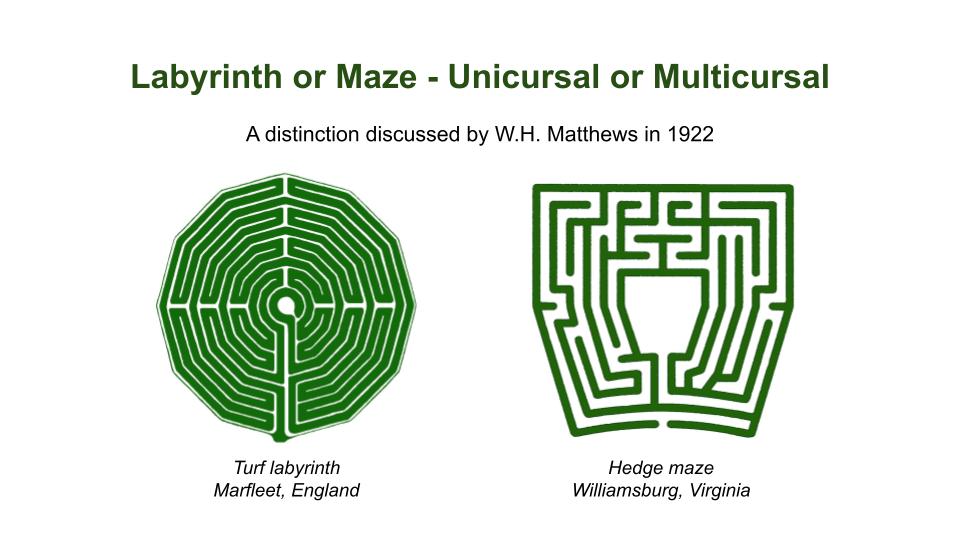

While people have been writing about labyrinths since the mid-1800s, the first person to really describe different types of labyrinths was W. H. Matthews in 1922—essentially a century ago now—when he defined the difference between what we now call labyrinths and mazes by pointing out that labyrinths are unicursal (one continuous path; a non-puzzle) and that mazes are multicursal (many branching paths; a puzzle).

The different types of labyrinths has been the subject of much more discussion.

Various people have tried to talk about these ideas, starting with some writers back in the 1950s and 60s. In Spain, John Heller and Stewart Cairns, for instance, did an interesting mathematical analysis of what we now call Classical labyrinths. Paul De Saint-Hilaire, who published several books in French in the 1970s through to the 1990s, broke labyrinths down into different types, but more based upon where they occurred than anything to do with their actual designs. Most of these early studies were restricted to specific types of labyrinths or were very generalised, and are now mostly outdated by modern research and developments.

In Scandinavia, where there are five to six hundred stone labyrinths that have been described, and in many cases preserved, there were lots of different types of labyrinths, albeit that they are nearly all based upon what we call Classical labyrinth designs. Consequently, John Kraft, Bo Stjernström, and several other researchers in Scandinavia have been working on a classification of those labyrinths that occur in northern Europe since the late 1970s. But their work was particularly concerned with the different types of stone labyrinths. They do notice things like, for instance, what we call Baltic labyrinths: labyrinths that have a path that comes in and then splits two ways and go into a double spiral, so that you can walk through the labyrinth and all the way back out again (rather than retracing your steps back out from the center).

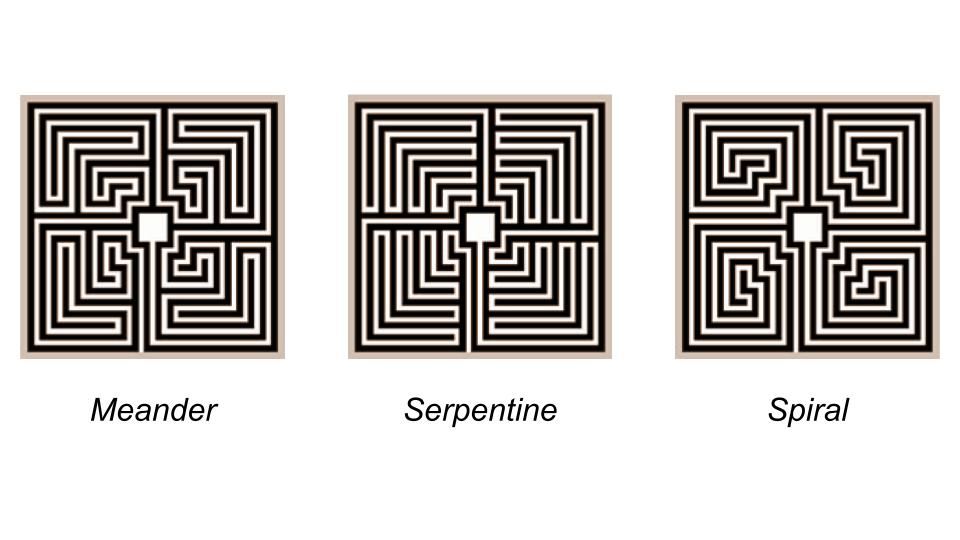

The Roman mosaic labyrinths are another group that have been studied. Wiktor Daszewski, John Kraft, and Anthony Phillips have all published papers on the Roman mosaic labyrinths, the types of designs that we now refer to as Roman. Daszewski’s study (1977) broke Roman mosaic labyrinths down into three groups: what he called meander, serpentine, and spiral (based on the repeated movement in each quadrant before going to the center).

Kraft’s study (1985) broke them down further into four distinct types, based on design, splitting meander types into simple and complex. Phillips’ papers (1988, 1992) were based entirely upon the mathematical structure of those labyrinths, and he found 25 distinct topological types from the 46 well-preserved mosaics that were part of his study.

Resources

Kern, Hermann. Labyrinthe. Munchen: Prestel, 1982.

Kern, Hermann. Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings over 5,000 years. Edited by Robert Ferré and Jeff Saward. Munich: Prestel, 2000.

Matthews, W. H. Mazes and Labyrinths: A General Account of Their History and Developments. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1922.

Matthews, W. H. Mazes and Labyrinths: Their History and Development. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1970. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46238/46238-h/46238-h.htm

Monteagudo, L. “Sistematización de Los Laberintos Prehistóricos.” Cuadernos de Estudios Gallegos VII (1952): 301–6. https://www.fundacionlmonteagudo.com/OBRAS_MONTEAGUDO/1952_sistematizacion_de_los_laberintos_prehistoricos_fundacion_luis_monteagudo.pdf

Phillips, Anthony. “The Topology of Roman Mosaic Mazes.” Leonardo 25, no. 3/4 (1992): 321–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1575858