What is a Labyrinth?

Labyrinths are an ancient archetype dating back 4,000 years or more. They are used symbolically, as a walking meditation, choreographed dance, or site of rituals and ceremony, among other things. Labyrinths are tools for personal, psychological, and spiritual transformation. They evoke metaphor, sacred geometry, spiritual pilgrimage, religious practice, mindfulness, environmental art, and community building.

Labyrinth carvings and constructions from hundreds to thousands of years old are found in numerous places around the world. There are similarities in the designs of these figures despite geographic and cultural differences and the passage of time. Global interest in labyrinths has ebbed and flowed, but there is something about these ancient symbols that keeps revitalizing that interest. The Classical labyrinths go back the furthest, the Roman and then Medieval labyrinths were later significant shifts in structure and materials, and now we are in a contemporary period of resurgence and innovation.

The essential features remain the same: a bounded, interior space clearly demarcated and different from the ordinary, exterior area, with a continuous though meandering path to the center and back out again, usually by the same path. A great variety of materials have been used to create labyrinths including stone, tile, grass, sand, earth, carved wood, and painted canvas. There are etched and mosaic labyrinths, finger and stylus labyrinths, and permanent, temporary, and portable walkable labyrinths.

Labyrinth or Maze?

Although the terms labyrinth and maze are often used interchangeably in English—and in some languages, there is only one word for both—we strive to make a distinction between the two. It is challenging to shift hundreds of years of cultural habit and understanding. It is important to remember that labyrinths pre-date mazes by thousands of years.

True labyrinths are unicursal—meaning that they have a single path—and are often intended to provide a meditative, reflective, and/or spiritual experience. The path may wind back and forth repeatedly, but there is no intended confusion and usually nothing blocking the view. Mazes are multicursal. They have multiple paths with choices and dead ends, and they typically serve as traps or games.

In some contexts, labyrinths have been used as protective symbols or traps for malevolent spirits. They can be presented as quiet, contemplative spaces or be associated with folk traditions including dances, or rendered in playful color schemes in community spaces including playgrounds. Labyrinths have been used as literary devices where they are depicted as labyrinths, yet described as mazes. So, it is no wonder that the two words are so intertwined.

Some labyrinth patterns, both historical and contemporary, have features outside of the standard form such as more than one opening between the exterior and interior, absence of a center space, intersections and path choices, or dual paths specifically for ceremonies or conflict resolution. Nonetheless, they may still be considered labyrinths, rather than mazes or simply paths, due to the intended use and effect of the design.

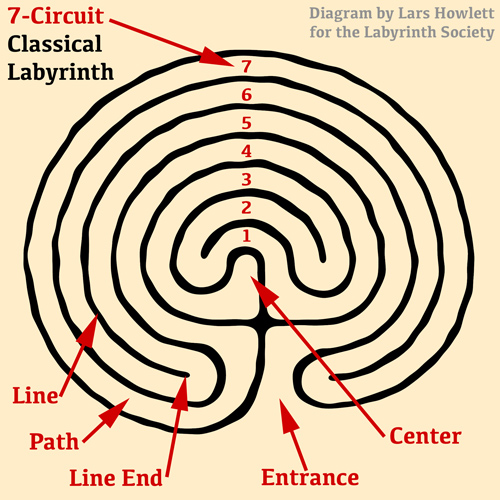

Labyrinths are named by type and can be further identified by their number of circuits. Counting from the center, the drawing at right illustrates a seven circuit design. You begin a labyrinth walk at the entrance and proceed along the path. Lines define the path and often maintain a consistent width, even around the turns. Generally at the center you have travelled half the distance, where it is common to pause, turn around, and walk back out again.

Left- or Right-Handed Labyrinths

A left- or right-handed labyrinth is determined by the direction of the first turn after entering the labyrinth. Jeff Saward estimates that approximately two-thirds of the ancient Classical labyrinths were right-handed (as depicted above) and two-thirds of the modern Classicals are left-handed. Neither is better than the other—it is totally up to personal preference.

An Ever-Evolving Typology

As our awareness of labyrinths expands, it is important to keep our terminology consistent. One example of a now outdated name is calling the Classical Labyrinth the Cretan labyrinth. Some people call the lines ‘walls,’ but as most labyrinths are two dimensional this can lead to confusion.

With this in mind, Jeff Saward and Sig Lonegren—with the help of Marty Cain, David Tolzman, Lea Goode-Harris, Alex Champion and Robert Ferré—began an ongoing dialog with the goal of providing clarity for a working labyrinth typology. Lars Howlett updated these resources also building off of the work of Erwin Reißmann and Andreas Frei.