Labyrinths in Places

Labyrinths are found in many places. Some are permanent and some are brought in temporarily for events. The challenge for labyrinth enthusiasts is often how to get permission to introduce a labyrinth into a specific environment. This section of the website examines some of the places where labyrinths may be found, the benefits of having them there, how they are used, and how people were able to install them there in the first place!

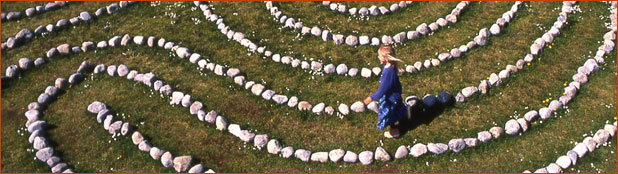

5. Outdoor Permanent Labyrinths

Building a permanent labyrinth at a university – and probably any public space – is likely to be the result of partnerships between sections of the organization that don’t often work together. This collaboration strengthens the project process (at the same time, making it more challenging) and therefore has the potential to strengthen relationships within the university in the longer term, a very positive benefit for labyrinth building and any complex project.

In every case, there will be powerful reasons for any university or college to install a permanent labyrinth. Such initiatives are likely to come from within the university, though, as the examples above show, they may include families and friends as contributors to these developments. In practice, of course, there may well be a combination of objectives that contribute in making a strong and ultimately successful case for a permanent labyrinth. In brief, there appear to be six key, sometimes inter-woven strands that have formed the basis for many successful bids:

- The labyrinth as a spiritual resource - meditative, contemplative or prayerful;

- The labyrinth as a memorial, an act of commemoration;

- The labyrinth as a beautiful feature of the landscape, enhancing the university or college campus or gardens;

- The labyrinth as a work of art;

- The labyrinth as a powerful form of outreach, creating strong links between the university or college and the community;

- The labyrinth as a resource for teaching and learning.

For more ideas and examples, see:

- Robert Ferré’s comprehensive overview of reasons to build a university labyrinth.

- An example of a proposal for a permanent labyrinth at the University of Central Oklahoma (USA)

- An example of fundraising for a permanent labyrinth at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth (USA)

Case Study 3

Critical factors in building a permanent labyrinth at the University of Kent, England

In the UK at the University of Kent, in south-east England, the labyrinth project began in 2007 as part of Dr. Jan Sellers' National Teaching Fellowship project, exploring aspects of reflection and creativity in student learning development. It later became part of the University's ongoing Creative Campus initiative.

An inter-disciplinary labyrinth group was set up, including student representation. Following initial research, the project drew on Fellowship funds to purchase a canvas labyrinth, having negotiated for a space to offer labyrinth walks. Interest amongst students and staff grew to such an extent that the University decided to install a permanent labyrinth as a resource for teaching and learning. Designed by Jeff Saward in collaboration with Andrew Wiggins, and completed August 2008, the Canterbury Labyrinth is also a wonderful work of art and has been used as a performance space for student-led theatre groups.

In seeking and building support for the building of a permanent labyrinth, there were some key factors that proved especially significant. (There is of course an element of subjectivity here; people with different roles within the University might list these differently).

Aesthetics. The labyrinth is a notable enhancement to the landscape – and the university environment.

Authority. The proposal went through appropriate formal channels and was supported by very senior colleagues.

Collaboration. The initiative has drawn together colleagues from very different sections of the University, and this breadth of support has been a critical factor.

Community. The new labyrinth has the potential to make a significant contribution to relationships between the City and the University.

Creativity. Kent rightly prides itself on being a creative university, and this is certainly a creative initiative.

Expertise. When we began to explore the idea – very tentatively – we found a highly respected team, ready to hand. Jeff Saward (researcher and designer) and Andrew Wiggins (Director of Haywood Landscapes) were developing a labyrinth for a local hospice and were available for a new project.

Incentive. Senior (and other) colleagues very much wanted to have the labyrinth ready in time for the Lambeth Conference, an international gathering of the world-wide Anglican community taking place every ten years. This desire for speed was valuable in accelerating the internal, practical measures and the decisions needed, once the go-ahead had been given in principle.

Innovation. Few universities - and none that I could find, in 2008 - have built a labyrinth specifically to support teaching and learning across the institution. Universities like to be innovative! The prospect of a possible ‘first’ gave significant impetus.

Ownership. It was crucial, with this initiative, that a well-established team within the University was committed and enthusiastic. At Kent, this was the University’s Unit for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching, where the Labyrinth Project is based. The project was then drawn into the newly evolving Creative Campus initiative, a natural home for it.

Serendipity. See ‘Expertise’.

Timeliness. The labyrinth provides a quiet time and space for reflection, much needed in a university life that feels increasingly pressured. There is a sense of the labyrinth being needed in this respect.

Universality. The labyrinth, with a history going back at least 3,500 years and a presence in many faith and cultural traditions, is truly a resource for the whole community – particularly important in a diverse, contemporary and secular university.

‘Rightness’. It’s hard to define this, but it seems right to say that the support for the initiative was overwhelming. People at all levels in the university came to feel that this was a good and achievable idea: something that was right for this university.

Prepared for the Labyrinth Society by Jan Sellers, lead editor of Learning with the Labyrinth (2016). Web pages revised 2018 by Jan Sellers, Jodi Lorimer, and Diane Rudebock. Visit Jan Sellers' website for more information.